Following readers' criticisms of the research behind the item "

Phew! How rats sigh when they're relieved" (see comments under previous post), the Digest invited lead author of that research, Dr. Stefan Soltysik, to defend his study. To continue the debate, please do use the 'comments' function at the bottom of this post. First, here's what Dr. Soltysik had to say:

I am grateful for the comments addressed to some aspects of the paper: “In Rats, Sighs Correlate with Relief.” I would like to initiate a dialogue to promote mutual understanding.

First about pain experiences in experiments.

In reply to those (Karen, Freya, Richard, Dave S.) justly concerned with the use of pain in behavioural experiments, I would like to offer a few words of explanation. This explanation does not apply to many studies where excessive electric shocks are used, but does apply to a great many behavioural studies, such as this one, in which the animals are required to exhibit normal emotional states.

The expression 'tail-shock' sounds bad if one does not realize that five brief and mild pain incidents per day is the least of unpleasant experiences the rats may go through in normal life. Not only do they inflict more harm on each other in normal fighting, but the effects of bites or scratches could be much more painful, prolonged, dangerous, and even lethal. Animals trained with the use of pain, such as in this study, are spared long-lasting unpleasant experiences of hunger, thirst, low or high ambient temperature, anxiety, cutaneous itch or swellings from lice or other parasites - all of which are normal in "natural life conditions."

Both I and my co-workers regularly tried the electric shock on ourselves. It wasn’t pleasant but was certainly preferable to a rat’s bite. Our entire experiment had to be very tolerable for the rats, because they needed to learn when it was safe and when not. They wouldn’t have been able to learn to relax and feel relief if the training was more disturbing. The same intensity of shock was used on cats in previous studies and to our surprise and satisfaction, many of these cats purred and fell asleep between trials. Both our cats and rats, when handled before and after the daily session, were quiet and friendly.

If it is accepted that there is a need to study emotional states of anxiety, fear and relief, then the administration - carefully and as humanely as possible - of pain is inevitable. Pain is not an abnormal experience – some cultural attitudes not withstanding – and a total lack of it (pain deprivation) may be deleterious to normal non-exaggerated responding to it and future coping with it.

As to the question of “scientific interest” and “benefit …. for humanity” (Karen, Louise) or replacing rats with humans (Dave Stevens – you probably think of paid volunteers, but I've even received suggestions of using inmates), consider this:

First, it is interesting per se, to find common psycho-physiologic grounds between our and other animals’ behaviour and “psyche.” Second, such commonality allows us to explore new ways (treatments, drugs) for dealing with human suffering (anxieties, depressions, phobias etc.). I do not know of any other procedure or behavioural test, or physiological index, that compares anxiety and relief, which would provide 20-fold (2000%) difference in objective measurements (it is usually measured in fractions, like 35% or so). Our rats sigh approx. 25 times/hour spontaneously, less than 10/h when anxious, but more than 180/h when relieved! So, consider, if you really have experimental animals` wellbeing in mind and not just negative feeling about any animal experimentation, that far fewer animals will be required to test a new psychotropic drug or some other procedure, when measuring emotional states (using sighs instead of heart rate, blood pressure etc.) is so dramatically improved (as demonstrated by the current study). And third, why not humans? Indeed, why not? I am sure now that rats have pioneered this approach, studies of human sighing should be considered as one of many other possible steps. But, humans seem diverged from other mammals (rats?) in that they use sighs in many emotional contexts: We sigh with relief, but also for something, to somebody, with disappointment, in frustrations, when resenting, etc. etc. That complicates things, unfortunately.Our paradigm that elicits in the rat three emotions (anxiety, fear and relief) reliably within 15 seconds of each trial has undeniable simplicity. So please, try to accept the possibility that mild aversive experiences and clear-cut highly significant results will benefit both humanity (leading to the fast reliable testing of new drugs) and animals (because fewer will be needed to obtain results).

Stefan Soltysik

You have read this article with the title 2005. You can bookmark this page URL http://psychiatryfun.blogspot.com/2005/11/why-perform-psychology-experiments-on.html. Thanks!

The Research Digest wishes all its readers a very Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. Hope you visit again in 2006!

The Research Digest wishes all its readers a very Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. Hope you visit again in 2006!

Whereas countless studies have examined the effect of negative psychological states on levels of cortisol – a corticosteroid hormone that is associated with stress and ill-health – few, if any, have looked at the effect of positive psychological states on the hormone, a fact that

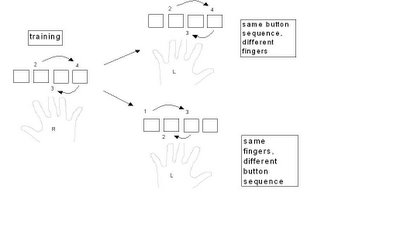

Whereas countless studies have examined the effect of negative psychological states on levels of cortisol – a corticosteroid hormone that is associated with stress and ill-health – few, if any, have looked at the effect of positive psychological states on the hormone, a fact that  A growing body of evidence suggests that we understand other people’s actions and intentions by simulating their movements in the motor pathways of our own brain. Now a study suggests that peripheral sensation and proprioception – the sense of where our limbs are in space – also play a role in this process, specifically when it comes to inferring other people’s expectations from the way they move.

A growing body of evidence suggests that we understand other people’s actions and intentions by simulating their movements in the motor pathways of our own brain. Now a study suggests that peripheral sensation and proprioception – the sense of where our limbs are in space – also play a role in this process, specifically when it comes to inferring other people’s expectations from the way they move.